Thanks to Alice Rose, research and documentation assistant in Archaeology at Hull Museums, I’ve had the opportunity to consult Hull and East Riding Museum‘s archives relating to the collections of Arthur E. Hastings Crofts (1849-1912) of Bradford. Crofts was a keen collector of pottery and glass, mainly Roman, from the Near East and Cyprus, and much of his collection passed to Hull Museums through a family bequest after his death.

Crofts’ correspondence is particularly interesting to me for its information about early 20th century networks of people collecting ancient Cypriot objects in Yorkshire and the Humber. He appears to have been initiated to the pleasures of collecting by William Cudworth, a local historian from Bradford, whom I’ve discussed before in connection with the Kent Collection in Harrogate. Cudworth seems to have recruited his friends and acquaintances as fellow collectors; he asks Crofts to ‘allow me to consider you as a pupil in the little school of archaeologists under my charge’, suggesting he saw himself as a leader in this area. Cudworth’s recommendations to his friend give an insight into his own collecting practices:

‘In collecting, keep to certain definite lines, instead of being tempted to acquire relics, however cheap, simply because they are old. Otherwise you only get a lot of curious things which lead to nowhere. In your case, you might adopt as Line 1 – Palestine, Line 2 – Cyprus, Line 3 – Roman remains in England. The first two might suffice.’

‘A lot of curious things which lead to nowhere’ might describe many antiquarian collections, but Cudworth evidently had greater intellectual ambitions. He was enthusiastic about Crofts’ progress in Cypriot collecting:

‘In Line 2 you are already at the top of the school. So far as Bradford is concerned, you lick the master into fits. Go on urging your friend ad lib. Like Oliver Twist always be wanting MORE.’

Letter from Cudworth to Crofts

© Hull and East Riding Museum: Hull Museums

Although Crofts diffused his collecting along several ‘lines’, he still managed to accumulate an impressive ancient Cypriot collection, much of which now belongs to Hull and East Riding Museum. Thanks to the excellent archival practices of both Crofts and the Museum, these objects have unusually rich collection histories, and can help to fill the gaps in our understanding of local, national and international Cypriot collecting networks.

As well as providing advice and guidance, Cudworth aided local collectors through his connection with the well-known dealer, ‘my London friend’, George Fabian Lawrence, best known for his role in relation to the discovery of the Cheapside Hoard. Lawrence regularly dispatched groups of objects from his dealership which Cudworth then sent on to his collecting friends, remitting funds to Lawrence for any sales made. The correspondence provides an insight into the domestic nature of this collecting, far removed from the archetype of the solitary antiquarian. Women’s voices are not heard in this archive, but their presences are detectable in the background; Cudworth mentions a piece which ‘Mr Fred Craven was taking away as a present to his wife’, and comments of a new purchase, ‘I hope Mrs Crofts will like [it] as well as yourself’. The collectors’ wives could hardly have been oblivious of the constant flow of ancient objects in and out of their houses, and may, to some extent, have been actively involved.

After Cudworth’s death in 1906, Crofts bought part of his collection, including Cypriot objects formerly part of the Lawrence-Cesnola collections. The Cesnola brothers’ publications seem to have been Cudworth’s main source of written information on ancient Cyprus, unsurprisingly for this period. He makes frequent references to A.P. di Cesnola’s Salaminia in describing objects from his collection; his edition of this work was donated to a local museum in 1951, and I am attempting to track it down.

Salaminia by A.P. di Cesnola

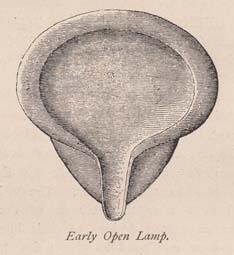

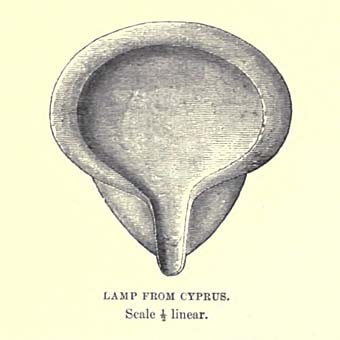

Crofts then took over Cudworth’s role as Lawrence’s Yorkshire correspondent, and received many dispatches of ancient objects, mainly lamps and glass. One striking aspect of this collecting activity is how hands-on the process of gaining knowledge was; Lawrence comments to Crofts of one consignment of lamps that ‘At least they will be instructive for you to look at, if you have no room’. Looking at and handling objects was the means of building up expertise.

In September 1908, Lawrence sent Crofts a series of lamps which were ‘the result of the digging of a Mr Pierides on his property at Curium Cyprus’. This is a most welcome archival sighting of Kleanthes Pierides, the source of many ancient Cypriot objects in the Kent Collection in Harrogate. Pierides wrote extensively to the British Museum and the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris to enquire about objects in his collection and the possibility of arranging sales, but it hasn’t previously been clear how his objects made their way to Yorkshire. In my paper for the ‘Classical Cyprus’ conference at Graz in 2017, I speculated that Pierides had sent objects to England through arrangements with private collectors, and it is interesting to get some insight into how this took place. A sale at Christie’s in 1908 included gold, gems, and glass, but not pottery of the kind found in the Kent Collection; it’s therefore very pleasing to hear from Lawrence in September 1908 that ‘I got what remains of the Pierides Coll at a lower rate than he wanted when he first came to London. His best went to Christies and sold well.’

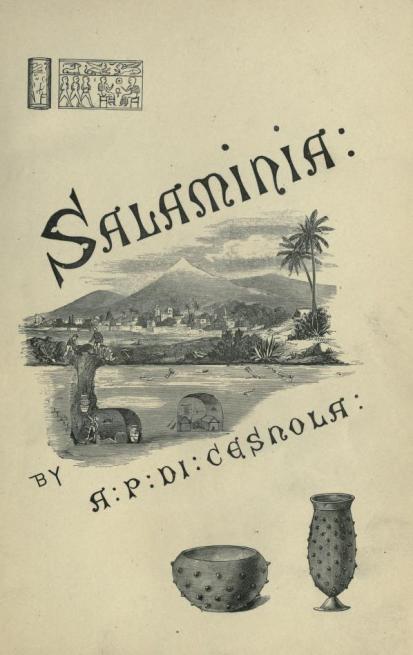

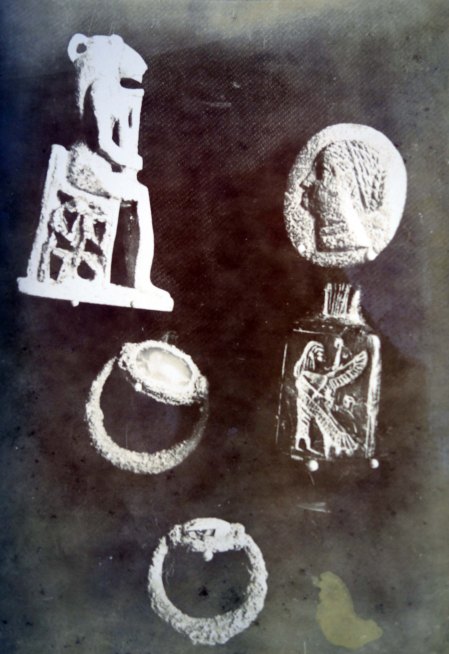

Crofts had already made more direct contact with Pierides in 1907 via J.R. Holmes, whom Alice has identified as a Bradford solicitor who moved to Cyprus and worked at the District Court in Limassol. From the tone of his correspondence, he appears to have been an old acquaintance of Crofts, and familiar with his collections. He gives a vivid description of Pierides’ collection, and suggests that Crofts should club together with local friends ‘so that you might buy for all and then the curios could travel in one parcel’. Most excitingly, photographs sent by Pierides survive in the Hull collection, evidently duplicates of those sent to his museum contacts but not preserved, alongside a list in Pierides’ handwriting of the objects he was prepared to sell.

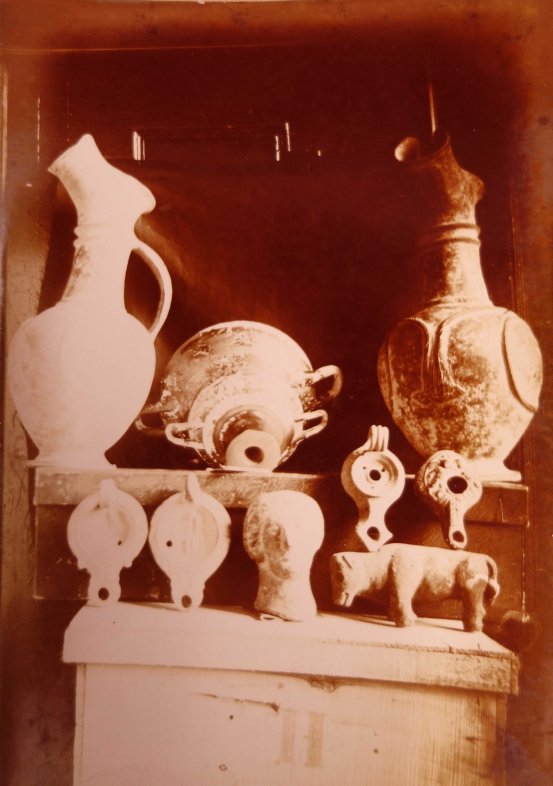

Photographs by Kleanthes Pierides of objects from his collection

© Hull and East Riding Museum: Hull Museums

The staging of the objects in this photograph is fascinating: propped on a desk against books and packets of photograph paper, in front of a painted background of a pillar and leaves. I would particularly like to see the object marked a.1, according to Pierides ‘a bronze vase Mycenaean piece, on the handle a human face, 7 inches’. All this can be cross-referenced against Pierides’ correspondence in the British Museum and the Cabinet des Médailles, and Olivier Masson’s research into Pierides’ collection and its destinations (CCEC 24), helping to fill some gaps in the overall picture of Pierides’ operations. The final stage of the journey of Pierides’ objects to the Kent Collection is still unclear, for now, but one of the photographs he sent Crofts includes an impressive pair of large Base Ring jugs, which can be identified with some confidence as those still in the Kent Collection today.

Photograph by Kleanthes Pierides of objects from his collection

© Hull and East Riding Museum: Hull Museums

Pair of Base Ring jugs from the Kent Collection, Harrogate

© Mercer Gallery, Harrogate

As a result of these rich and detailed archives, the networks of Cypriot collecting are coming into clearer focus. These ‘second generation’ collectors benefited from the influx of objects into the UK from the Cesnola brothers’ sales from 1871 to 1892, and the importation and later dispersal of the collections of consular and early colonial residents on Cyprus. Pierides’ correspondence also suggests that, paradoxically, the 1905 Cypriot Antiquities Law prompted the sale overseas of his collection, though this claim may also have been part of his sales technique. These small collections tended to make their way to local museums after the deaths of their collectors, where their institutional settings gave them new contexts and audiences, and began a new phase of their histories.