Like so many others, I’m excited to get back to visiting museums and galleries, travelling by train, going to other cities, and generally picking up some of the activities that have been inaccessible for many months now. I took a welcome step in this direction yesterday with my first visit to the Leeds Museums Discovery Centre for over a year. I had no idea when I visited in February 2020 that it would be the last time until my thesis was nearly finished, so I had a lot of ground to make up. I’m really grateful to Kat, the curator of archaeology, for getting me in at the first opportunity!

It was fantastic to be back in the research room, and to have the chance to get hands on with objects again. I had previously come across records for a small group of unidentified ceramics, many of them associated with John Holmes, one of the main collectors behind the ancient Cypriot collection, so I was keen to take a look at them. Most of them looked Romano-British, in my decidedly non-expert opinion, including one labelled ‘Anglo-Roman, Colchester’, for which we can probably take Holmes’ word. However, one object, described as a ‘small red cup with flat handle’, definitely rang a few bells.

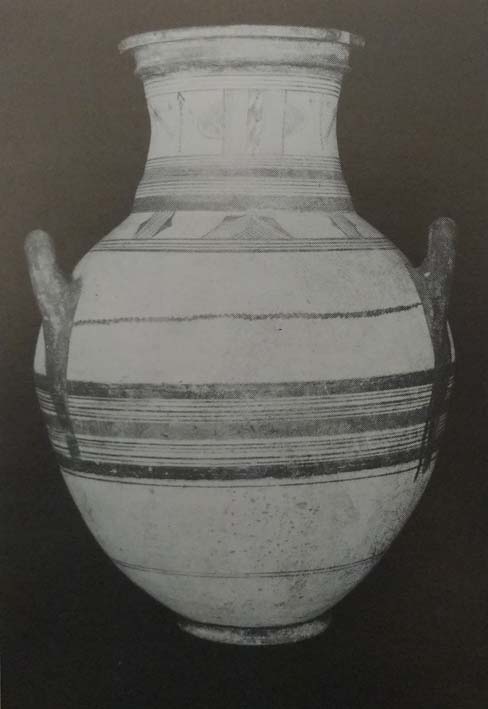

It’s a handmade Late Bronze Age Base Ring tankard, with a biconical body, a wide neck with a flat rim, a delicate ring base and a strap handle. The fabric has that distinctive metallic Base Ring ‘ting’, and it’s fired with a patchy red-brown slip.

Rather endearingly, the applied rings of decoration below the rim are a bit slapdash at the ends near the handle, and the whole thing is somewhat wonky.

There’s a break across the width of the handle at the join to the rim, and it seems quite likely that there would have been a thumb grip there, which has now been lost. It can be compared to a similar tankard in the British Museum’s collection.

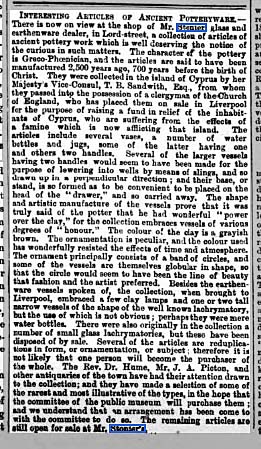

It’s marked with ‘Hs’ on the base, which is John Holmes’ mark, so it can be securely identified as part of his collection. It may originally have come from T.B. Sandwith‘s collection, and perhaps from the region around Dali, where Sandwith collected and where the British Museum’s tankard is from, but this can only be speculative.

One thing that’s become clear while working on my thesis is how fluid the boundaries of a collection such as this are, where there is very little archaeological provenience, and the provenance history is complex with many gaps in the documentation. Some collections come straight from an archaeological dig to a museum, and so their identities are never in doubt, but the identification of a historic collection such as this inevitably involves quite a lot of subjective judgment. This relates both to the objects themselves – how plausible is it that they were made or found on Cyprus? – and their provenance or collection history – how confidently can we trace them back to Cyprus? I’ve called this ‘the last ancient Cypriot pot’ because it’s the last addition to my thesis – I do most sincerely hope – and marks the point at which I’m drawing a boundary around the ancient Cypriot collection for now. But I am quite sure that my assessment of which objects are in and out of the collection will be challenged and modified in the future, not least by me. The end of the thesis is not the end of the story!

Harrogate Museums and Arts, Harrogate Borough Council

Harrogate Museums and Arts, Harrogate Borough Council