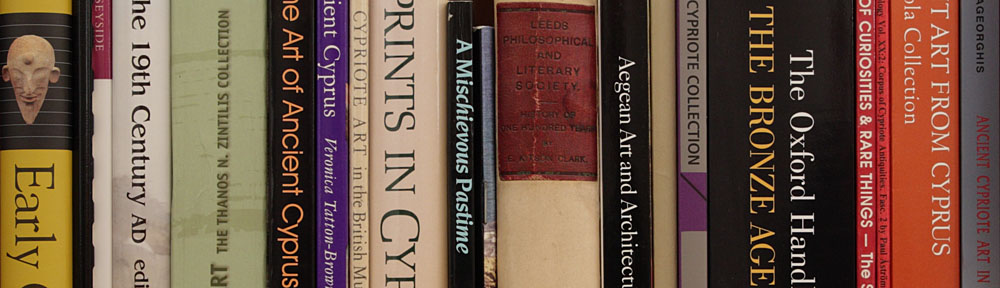

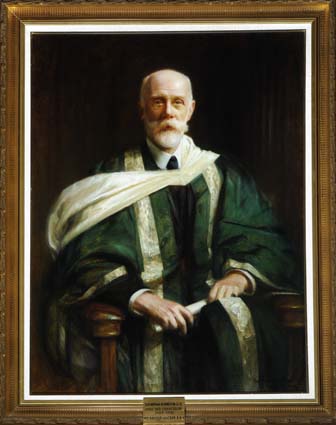

Why does the University of Leeds have an ancient Cypriot collection? The answer involves some detective work, and hinges on the interests and networks of Sir Nathan Bodington, first Vice-Chancellor of the University. This part of the story begins just over a century ago, in October 1913.

The University of Leeds’ archives record a visit made by the second Vice-Chancellor, Michael Sadler, to Lady Eliza Bodington, widow of Sir Nathan Bodington who had died in 1911, two years before. They enjoyed a gossip about University matters, and Lady Eliza raised the subject of ‘a very interesting collection of early pottery from Cyprus’. She explained how they came to Leeds:

“They were apparently ordered by Sir Nathan Bodington from a friend in Cyprus for the great University bazaar. They arrived late. The case was put in the cellar of the University and overlooked.”

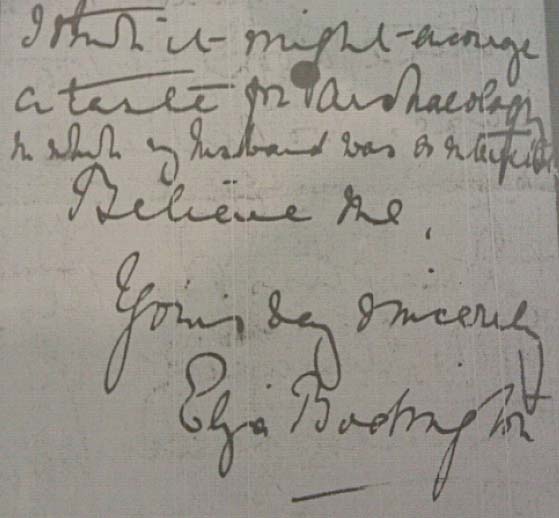

Lady Eliza wanted to give part of the collection to the ‘Classical Department’, and the rest to the Leeds Girls’ High School. Her hope was that ‘they may be the beginning of a Classical Collection’ and ‘might encourage a taste for archaeology in which my husband was so interested’.

The help was enlisted of Mr A. M. Woodward, newly appointed Lecturer in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Leeds. He produced a list of the collection, 35 items in all, along with valuations (presumably for insurance purposes) ranging from 4/6 to 110/-. This list includes 19 ceramics, two figurines, one alabastron, seven pieces of glass, two of bronze, and four knucklebones, ‘well preserved’. His descriptions are rather broad, but the objects still remaining in the University’s collection can be mapped to his list with a fair degree of confidence. The remaining 11 items – some of the ceramics and glass, the figurines and those knucklebones – were presumably donated to the Leeds Girls’ High School in accordance with Lady Bodington’s wishes, although the school’s archivist has not found any trace of this donation.

Three of the ceramics were given to Mr Woodward in fragments, which he repaired and gave to be displayed and insured with the rest of the collection. He appears to have been very versatile as a classicist, publishing on archaeology, epigraphy, and numismatics, and ranging across the Peloponnese, Attica, and Asia Minor, so perhaps it’s no surprise that he was able to turn his hand to a competent repair of ancient Cypriot pottery, which has survived well to this day.

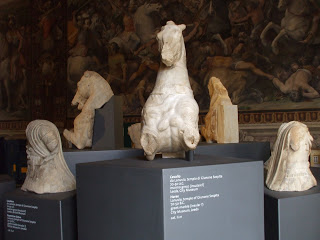

Sir Nathan Bodington’s role in connection with these artefacts is entirely in line with his lifelong interest in the ancient world. He went to Oxford as an Exhibitioner in Greek, and took a First in Literae Humaniores, and, as a friend put it, ‘he remained to the last a true lover of the classics, and especially of Greece and its art.’ He was a member of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society for 25 years, and its its President from 1898-1900. He addressed the Society on subjects including ‘The Mycenaean Age in Crete’ and ‘The Story of Lanuvium’, and was instrumental in obtaining ancient artefacts for its Museum, including part of the Savile Collection of Antiquities from Lanuvium, still to be seen in the Leeds City Museum today.

His interest in antiquity extended beyond the Society’s business; the Leeds Mercury for Saturday November 8th 1890 records him chairing a talk on the Parthenon Marbles at the Yorkshire College by the famous Classical scholar Jane E. Harrison, and also draws attention to his article in that month’s Macmillan’s Magazine on ancient Ventimiglia. After his marriage in 1907, the couple toured extensively in the Mediterranean, often visiting ancient sites. In 1908 they spent two weeks on an archaeological dig at the Cawthorn Roman camps, and appear to have thoroughly enjoyed themselves:

“he was intensely happy living this simple life, and a junior member of the staff… discovered to [his] surprise that the holder of the dignified office of Vice-Chancellor could revel in a picnic holiday with a keen sense of humour and making light of all difficulties.”

(W.H. Draper, Sir Nathan Bodington: A Memoir).

Bodington himself collected a few ancient artefacts in Cyprus, which Eliza Bodington donated to the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society in 1913, after his death. Given this lifelong interest in the ancient world, it’s highly plausible that Nathan Bodington would have the contacts and interest to obtain an ancient Cypriot collection. His biographer emphasises the huge workload he laboured under, making it not implausible that a small collection like this, perhaps not seen as particularly valuable or significant, could have been overlooked on its arrival in Leeds.

However, I am not wholly convinced by the story of the ‘Grand University Bazaar’ as the reason for the objects’ purchase. Delving in the University’s archives has as yet failed to identify this Bazaar, although it might well be one ‘held under the auspices of the Student’s Athletics Union’ in May 1895, which raised the significant sum of £1,810 for athletics premises and equipment. It’s important to bear in mind that Nathan Bodington had died two years before the case in the cellar came to light, so no-one knew for sure what his intentions had been.

I think there’s another explanation for the University of Leeds collection, one which accounts for another set of mysteriously missing artefacts, and helps make sense of the dates, styles and markings of the objects which survive. More on this next time!