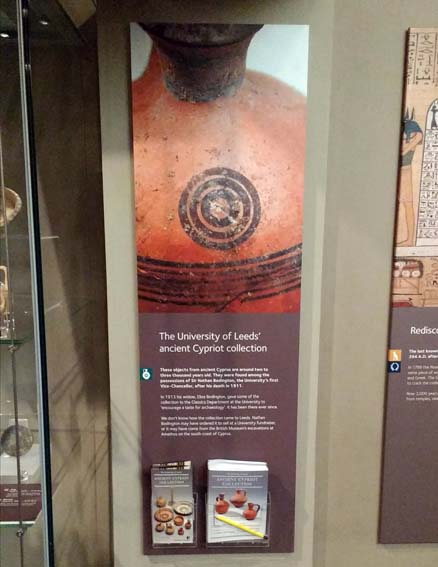

As previously mentioned, the Leeds University ancient Cypriot collection came to light in the University’s cellars in 1913, where Lady Bodington supposed it had been overlooked since her husband, Sir Nathan Bodington, ordered it for a University fundraising event.

This may well have been the case; but there’s an alternative explanation, which might also help to account for another mysteriously overlooked collection. The British Museum sponsored excavations at Amathus in Cyprus in 1893-94, led by J.L. Myres and A.H. Smith. In 1895 the Trustees agreed to a proposal from A.S. Murray, Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities, to donate objects from these excavations to a range of museums, colleges and universities around the country. These included the Yorkshire College, Leeds, of which Nathan Bodington was the Principal. A letter from Nathan Bodington accepting the offer on behalf of the College survives in the British Museum’s archives.

The trail then goes cold; there is no record of the collection arriving in Leeds, or trace of it in the College’s annual record, although this generally gives full details of all donations. The Museum of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society was often used by the Yorkshire College’s students, but again, the Society’s annual report makes no mention of any donation. This contrasts with the treatment of a further gift of Cypriot antiquities from the British Museum in 1902 to the Museum of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, which is written up in full in that year’s annual report.

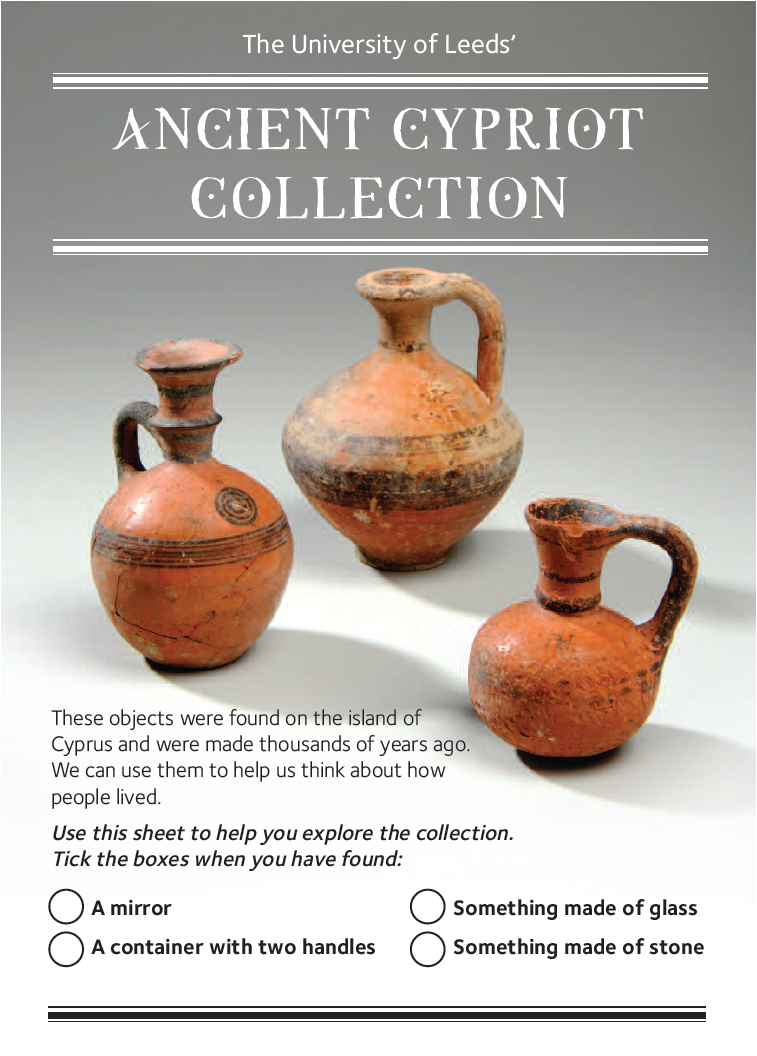

Given this silence in the official records, it seems at least possible that the University’s collection is this same donation from the British Museum’s excavations in Amathus. There’s no way of knowing for sure; but there are a few factors which tie in with this theory. The collection covers the right timescale, from the Cypro-Geometric to the Roman period. Also, some of the pottery is decorated in a style typical of Amathus, with freely applied red and brown stripes and circles on a background of buff slip.

UNIV.1913.0013

Bowl with decoration typical of Amathus

© University of Leeds

There are also some parallels between surviving objects in the University of Leeds collection, and those of other museums and colleges who were sent donations from Amathus by the British Museum in 1895. That said, there are plenty of objects in those collections which aren’t reflected in the surviving University collection; for example, there are no figurines. However, Lady Bodington intended to give part of the collection to the Leeds Girls’ High School, and this may well have filled in some of the gaps.

The British Museum possesses Myres’ notebooks from his excavations in Amathus, which provide brief records of tomb contents, and illustrations of unusual pieces. These raise a number of tantalising possibilities; could the University of Leeds jug marked 292 be one of the ‘2 small painted jugs’ recorded by Myres in the tomb of that number?

UNIV.1913.0002

Jug marked ‘292’

© University of Leeds

And could the unusual Punic one-handled jug, probably an import from Carthage, be the ‘jug of red clay’ illustrated by Myres from Tomb 291?

UNIV.1913.0033

Punic jug

© University of Leeds

Myres notesbook, Tomb 291 – ‘1 jug of red clay’

© British Museum

On the face of it, it seems unlikely; the British Museum donated duplicates, i.e. common items, to other institutions, rather than anything out of the ordinary; but there is certainly a similarity between the shape of the Leeds jug and Myres’ sketch.

Whether or not this collection originated from Amathus, it merits research and a higher profile, not least to honour Nathan Bodington’s contribution to the study of the ancient world in Leeds, which prompted Lady Bodington’s donation. Just over a century after its rediscovery, the collection is entering a new phase of its existence with new opportunities to ‘encourage a taste for archaeology’, in line with her wishes.