Thanks to a tip-off from the Alexander Malios Research Institute, I recently came across this Black on Red flask from the Garstang Museum in Liverpool, which is featured on the Museum’s Sketchfab site.

Garstang Museum Black on Red flask

Sketchfab is a great way of making objects accessible – even more so, in some ways, than having them on display (many’s the time I’ve awkwardly crouched to see the bases of objects through glass shelves).

Unsuccessful photo of object labels at the Manchester Museum

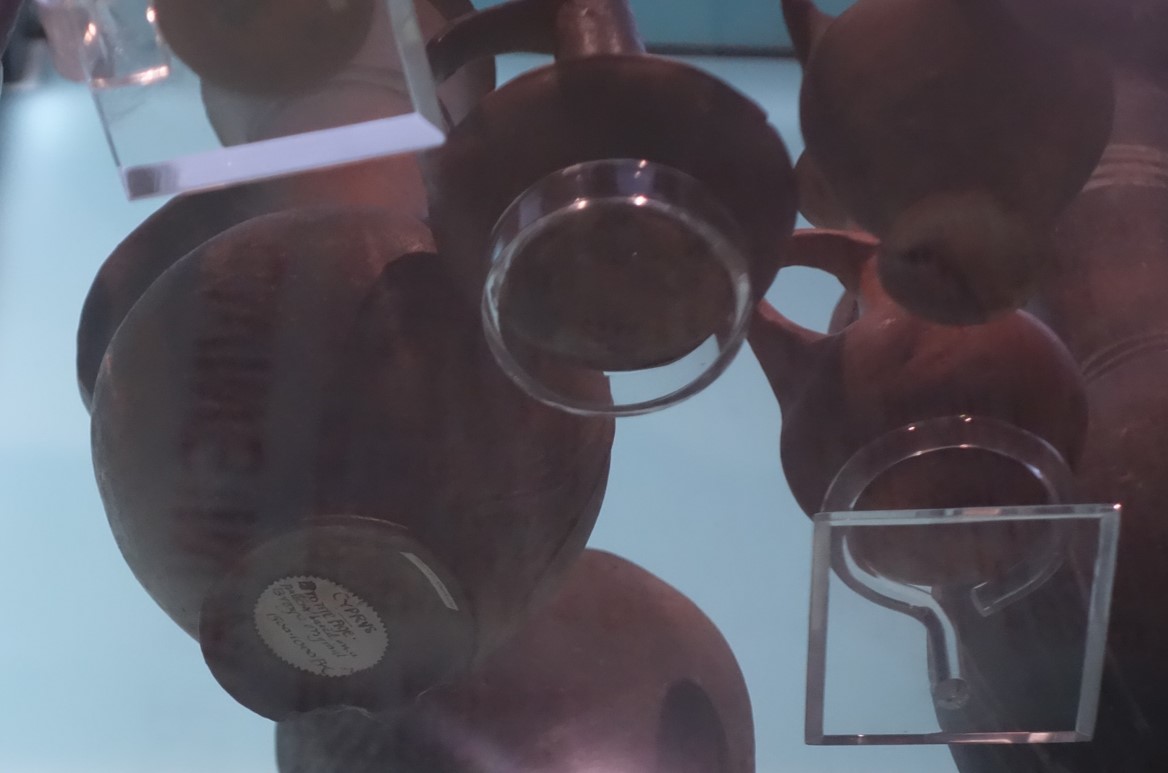

I’d really like to try Sketchfab for the University of Leeds ancient Cypriot collection, it would be a brilliant project to do with undergraduates, though the prospects look rather remote at the moment. One of its major advantages is that you can look at the object from all angles – including a good look at this label on the base of the flask. It’s always exciting to find a label on an ancient Cypriot object, as a clue to its travels, and this one looks very familiar.

Label on base of Black and Red flask, from the Garstang Museum

It identifies this flask as having been on display in the 1875 Yorkshire Exhibition of Arts and Manufactures in Leeds, alongside other objects from Cyprus put up for sale by Thomas Backhouse Sandwith, HM Consul on Cyprus from 1865 to 1870, in order to raise money to relieve famine on the island. It formed part of a large display of Cypriot antiquities, including what must have been quite an extensive range of Black on Red ware. In the Official Catalogue to the Exhibition, these were described, with more enthusiasm than precision, as:

‘…a series of vessels and objects not readily classified. They are generally water bottles, scent, oil, or colour vessels, of a fine, red smooth body and slightly varnished, with ornaments of rings and circles, both horizontal and vertical, in black. The workmanship of this class of pottery exhibits a high skill, and the variety of circling is most profuse and effective.’

Many people bought Sandwith’s objects from the 1875 Exhibition – serious and casual collectors, those who wanted to know more about the ancient past, and those who simply admired the appearance of the objects. Parts of the collection were loaned or given to museums in York, Halifax and Sheffield when the Exhibition closed, and many objects were later dispersed in sales. Before the Exhibition took place, some of Sandwith’s objects were sold at a dealer’s shop in Liverpool in 1870, and some of these were bought for the Liverpool Free Public Museum. A Mr G. Sinclair Robertson seems to have bought at least one ancient Cypriot vessel directly from Sandwith’s brother in 1870, and probably donated it to the Liverpool Museum in 1876. But this flask had a different route, which ended not at the Liverpool Museum, but at the Garstang Museum, then known as the Liverpool Institute of Archaeology, a library and museum founded by John Garstang in 1904 as a resource for archaeology at the University of Liverpool. Garstang (1876-1956) was an archaeologist who excavated in Egypt and the Sudan, Anatolia and Palestine. He was skilled at fundraising for excavations and other projects, and managed to muster private support for his new Institute.

Cypriot pottery was sent to the Institute from the government of Cyprus in 1904, and from the Cyprus Museum in 1922, but this flask wouldn’t have been part of either of these donations, having been in the country since at least 1875. It might have formed part of the founding collections, perhaps part of a larger donation, or might have come to the Institute at a later date. Research in the Museum’s archives – sadly not possible under present circumstances – could perhaps shed some light on this; my guess would be that it was donated from a miscellaneous collection of antiquities that had outlived the enthusiasm of its original purchaser. The disparate collections put together in the 19th century often caused difficulties for their inheritors, and transferring them to a public institution was a common solution, forming the basis of many of the public collections that survive today.

This flask is no. 117 in Mee and Steel’s 1998 catalogue of the collection, which gives the provenance as ‘unknown’, and doesn’t mention the Yorkshire Exhibition. We don’t know anything for sure about the archaeological provenance of the flask (though we could speculate on the basis of the evidence, albeit patchy, for Sandwith’s explorations and collecting in Cyprus), but this record reflects changing approaches to the history of Cypriot archaeology, and the relatively recent growth of interest in the history of collections. Labels are a gift to the researcher, and I hope that as more collections become digitised – both their information, and the objects themselves – they’ll become easier to discover.